The following is an excerpt from Chapter 3 of Gleanings in Buddha Fields, the collection of essays from Lafcadio Hearn, published in 1897.

His meditation on the origins and quality of simple pleasures that he found during the Meiji period, and which still enchant the visitor to Japan today, are instructive for our own age, wherein we have become desensitized to the wonder of life and the most basic sources of enjoyment all around us.

Please enjoy!

While I was thinking about the fugitive charm of Japanese amusements, the question put itself: Are not all pleasures keen in proportion to their evanescence?

We know that mental enjoyments are powerful in proportion to the complexity of the feelings and ideas composing them; and the most complex feelings would therefore seem to be of necessity the briefest.

At all events, Japanese popular pleasures have the double peculiarity of being evanescent and complex, not merely because of their delicacy and their multiplicity of detail, but because this delicacy and multiplicity are adventitious, depending upon temporary conditions and combinations.

Among such conditions are the seasons of flowering and of fading, hours of sunshine or full moon, a change of place, a shifting of light and shade.

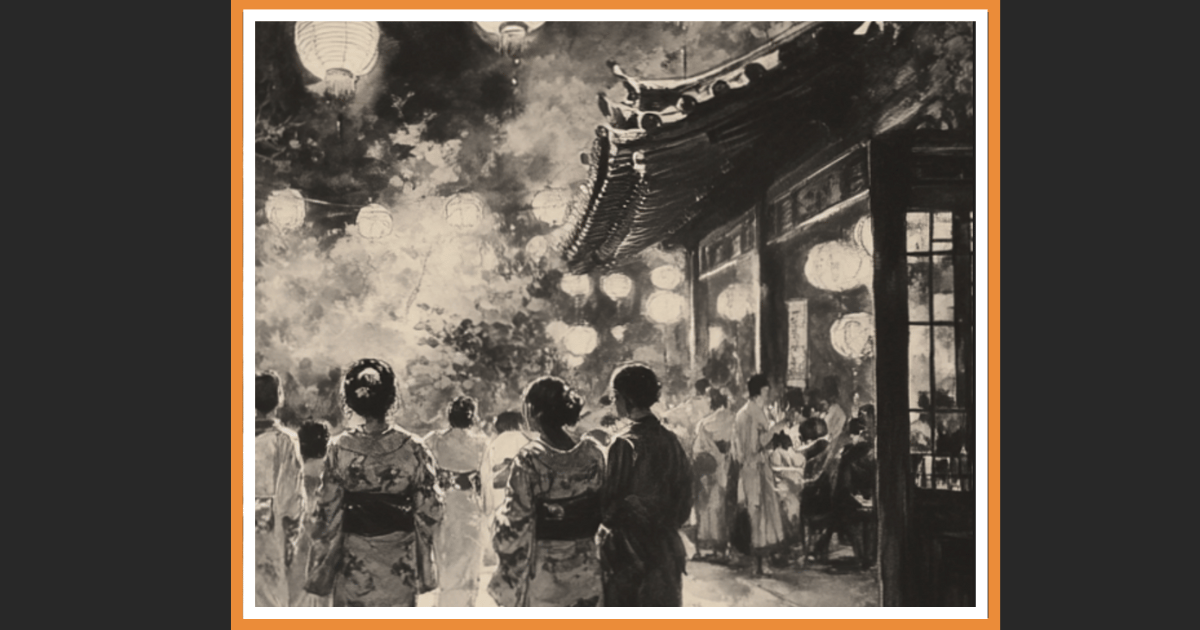

Among combinations are the fugitive holiday manifestations: fragilities utilized to create illusion; dreams made visible; memories revived in symbols, images, ideographs, dashes of color, fragments of melody; countless minute appeals both to individual experience and to national sentiment.

And the emotional result remains incommunicable to Western minds, because the myriad little details and suggestions producing it belong to a world incomprehensible without years of familiarity—a world of traditions, beliefs, superstitions, feelings, ideas, about which foreigners, as a general rule, know nothing.

Even by the few who do know that world, the nameless delicious sensation, the great vague wave of pleasure excited by the spectacle of Japanese enjoyment, can only be described as the feeling of Japan.

A sociological fact of interest is suggested by the amazing cheapness of these pleasures. The charm of Japanese life presents us with the extraordinary phenomenon of poverty as an influence in the development of aesthetic sentiment.

But for poverty, the race could not have discovered, ages ago, the secret of making pleasure the commonest instead of the costliest of experiences—the divine art of creating the beautiful out of nothing!

One explanation of this cheapness is the capacity of the people to find in everything natural—in landscapes, mists, clouds, sunsets—in the sight of birds, insects, and flowers—a much keener pleasure than we, as the vividness of their artistic presentations of visual experience bears witness.

Another explanation is that the national religions and the old-fashioned education have so developed imaginative power that it can be stirred into an activity of delight by anything, however trifling, able to suggest the traditions or the legends of the past.

Perhaps Japanese cheap pleasures might be broadly divided into those of time and place furnished by nature with the help of man, and those of time and place invented by man at the suggestion of nature. The former class can be found in every province, and yearly multiply.

Some locality is chosen on hill or coast, by lake or river: gardens are made, trees planted, resting-houses built to command the finest points of view; and the wild site is presently transformed into a place of pilgrimage for pleasure-seekers. One spot is famed for cherry-trees, another for maples, another for wistaria; and each of the seasons—even snowy winter—helps to make the particular beauty of some resort.

The sites of the most celebrated temples, or at least of the greater number of them, were thus selected—always where the beauty of nature could inspire and aid the work of the religious architect, and where it still has power to make many a one wish that he could become a Buddhist or Shinto priest.

Religion, indeed, is everywhere in Japan associated with famous scenery: with landscapes, cascades, peaks, rocks, islands; with the best places from which to view the blossoming of flowers, the reflection of the autumn moon on water, or the sparkling of fireflies on summer nights.

I asked at a doll-maker's for twenty tiny paper dolls, each with a different coiffure—the whole set to represent the principal Kyōto styles of dressing women's hair. A girl went to work with white paper, paint, paste, thin slips of pine; and the dolls were finished in about the same time that an artist would have taken to draw a similar number of such figures: the image in the brain realized itself as fast as the slender hands could work.

Thus most of the wonders of festival nights are created: toys thrown into existence with a twist of the fingers, old rags turned into figured draperies with a few motions of the brush, pictures made with sand. The same power of enchantment puts human grace under contribution. Children who on other occasions would attract no attention are converted into fairies by a few deft touches of paint and powder, and costumes devised for artificial light. Artistic sense of line and color suffices for any transformation.

But the whole exhibition is as evanescent as it is wonderful. It vanishes much too quickly to be found fault with. It is a mirage that leaves you marveling and dreaming for a month after having seen it.

Perhaps one inexhaustible source of the contentment, the simple happiness, belonging to Japanese common life is to be found in this universal cheapness of pleasure.

The delight of the eyes is for everybody. Not the seasons only nor the festivals furnish enjoyment: almost any quaint street, any truly Japanese interior, can give real pleasure to the poorest servant who works without wages.

The beautiful, or the suggestion of the beautiful, is free as air. Besides, no man or woman can be too poor to own something pretty; no child need be without delightful toys. Conditions in the Occident are otherwise.

In our great cities, beauty is for the rich; bare walls and foul pavements and smoky skies for our poor, and the tumult of hideous machinery—a hell of eternal ugliness and joylessness invented by our civilization to punish the atrocious crime of being unfortunate, or weak, or stupid, or overconfident in the morality of one's fellow-man.

Ink & Time brings you forgotten works of literature and culture to enrich your experience of life and improve your critical thinking.