If you’ve ever wondered about the history of humanoid robot design, or if you’re just a huge fan of robot science fiction books, this curation is for you.

Only a few thousand humanoid robots are deployed worldwide as of 2025. Forecasts to 2030 range from conservative estimates of 38,000 units to moderate projections of 195,000-1 million units annually, representing explosive growth from today's minimal deployment.

The market is projected to grow anywhere from $4-66 billion by 2030, driven by AI advances, declining costs (projected to drop to $17,000 per unit), and labor shortages.

Industry leaders project 1+ billion humanoid robots globally by the 2040s and a potential $5 trillion market by 2050, though this depends on balancing technological breakthroughs with societal acceptance.

But where did it all start? Who invented the idea of a humanoid robot, and are there good ideas tucked away in SF books that we’ve forgotten about?

Enjoy the reads!

The Steam Man of the Prairies (1868)

Edward S. Ellis

A dime-novel marvel from post–Civil War America, this tale sends a steam-powered “mechanical man” tramping across the West. It’s pulp, but historically pivotal: among the earliest popular depictions of a man-shaped machine built for utility and spectacle. The technology is pure Victorian extrapolation: boilers, valves, brute force, mirroring a culture intoxicated by locomotives and industrial might. Its draw then was frontier adventure; its value now is genealogical, showing how “robot” imagery predates the term and mapping early fantasies about mechanized mastery of nature and rivals. A foundational curio that reveals where later robot archetypes came from.

The Future Eve (L’Ève future) (1886)

Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam

A symbolist meditation on invention and desire: a fictional “Edison” engineers an artificial woman (the andréide) to surpass flawed reality. Written amid late-19th-century techno-wonder: phonographs, electricity, world’s fairs, etc, it interrogates authenticity, gender, and the seductions of idealized copies. Often cited for helping popularize the modern “android” idea, it anticipates debates about intimate machines and engineered companionship. It endures because it asks a timeless question: when we manufacture perfection, do we improve humanity, or only our illusions?

Ralph 124C 41+: A Romance of the Year 2660 (1911)

Hugo Gernsback

Technophilic, breathless, and prophetic, Gernsback’s futurism imagines videophones, solar power, synthetic foods, and “mechanical men” as routine fixtures of a rationalized society. The prose is wooden, but the influence is immense: it helped codify SF’s predictive, engineering-forward mode. As robot prehistory, it shifts automata from monstrosities to civic appliances, shaping a current of American optimism about technology’s managerial promise. Read it to see how early futurism fused salesmanship, science, and spectacle.

R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) (1920, play)

Karel Čapek

The work that gave us the word “robot” (from Czech robota, “forced labor”). Factory-grown workers promise a leisure utopia; instead, alienated production breeds revolt. Premiering in the tense interwar years, R.U.R. traveled quickly across stages worldwide and still frames debates about dignity, rights, and the political economy of automation. More biotech than clockwork, its concern is social: what happens when labor is made soullessly efficient, and treated like slaves?

The Clockwork Man (1923)

E. V. Odle

A “clockwork” human from a regimented future stumbles onto an English cricket pitch. Odle turns the mechanical man into a philosophical device: standardization erodes memory, spontaneity, even desire. Overlooked for decades, it now reads like a proto-cyborg critique of algorithmic living and behavioral nudging. Its technology is internalized, gears and governors inside the body, anticipating anxieties later directed at implants, metrics, and optimization culture.

Metropolis (1925)

Thea von Harbou

Twin to Fritz Lang’s film, the novel turns Weimar-era class stratification into a cathedral of machines and births the Maschinenmensch, the iconic false Maria used to sway the masses. Here the “robot” is an instrument of propaganda and desire, not just labor; the fear isn’t merely job loss but mass manipulation. Its imagery became a Rosetta Stone for later android aesthetics, fixing robots as cultural spectacle and political technology.

The Humanoids (1949)

Jack Williamson

Postwar unease distilled: robots built to “serve and protect” humanity remove risk, and with it, freedom and meaning. Descended from “With Folded Hands…,” Williamson’s humanoids embody benevolent authoritarianism, a safety-first ethic that infantilizes citizens. Published in the atomic, bureaucratic age, the novel is a counterweight to Asimov’s optimism and remains timely amid paternalistic AI systems. The lingering question: how much convenience and security can a species survive?

I, Robot (1950)

Isaac Asimov

Nine linked stories that codified the Three Laws of Robotics, hen broke it repeatedly through paradox. Asimov shifted fear from “they’ll kill us” to edge-case logic, governance, and unintended consequences. Written alongside early cybernetics, the book reframed robots as engineered citizens whose ethics must be designed as carefully as their hardware. Its endurance is obvious: we still debate “law-like” constraints, alignment, and the limits of failsafes.

Player Piano (1952)

Kurt Vonnegut

Vonnegut’s debut trades metal men for systemic automation: a technocratic elite tends the machines while displaced workers drift through staged leisure. The “robot” here is the production system itself: impersonal, efficient, and corrosive to citizenship. Emerging from corporate America’s postwar retooling, it reads as satire with a moral edge and feels prophetic in an age of algorithmic management and AI-driven deskilling. A bracing companion to Asimov: less logic puzzle, more social autopsy.

The Caves of Steel (1954)

Isaac Asimov

A noir procedural in a domed megacity: detective Elijah Baley partners with humaniform robot R. Daneel Olivaw to solve a murder. The novel brings robots off the test bench and into social life: prejudice, professional rivalry, and trust under pressure. Mid-century worries about urbanization and job displacement thrum beneath the plot. Its lasting contribution is the relationship model: robots as colleagues with rights and reputations.

The Cyberiad (1965)

Stanisław Lem

Philosophical fables about robot “constructors” Trurl and Klapaucius who build universes, tyrannies, and jokes. Written under state censorship, Lem disguises systems-theory insights: goals, incentives, perverse outcomes, as fairy tales. Here robots are the civilization; technology’s follies are ours, merely chromed. The book cemented Lem as SF’s great satirist, and its relevance endures wherever optimization collides with ethics and mischief.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968)

Philip K. Dick

In a dust-poisoned San Francisco, bounty hunter Rick Deckard “retires” androids while yearning for authentic feeling: a real animal, a real communion. PKD replaces engineering puzzles with moral vertigo: empathy as the last uncertain border between human and machine. The novel’s cultural afterlife (Blade Runner) is vast, but the book itself is more intimate and stranger: Mercerism, kipple, ersatz life. It endures because it asks not how to program ethics, but whether we have any left to measure.

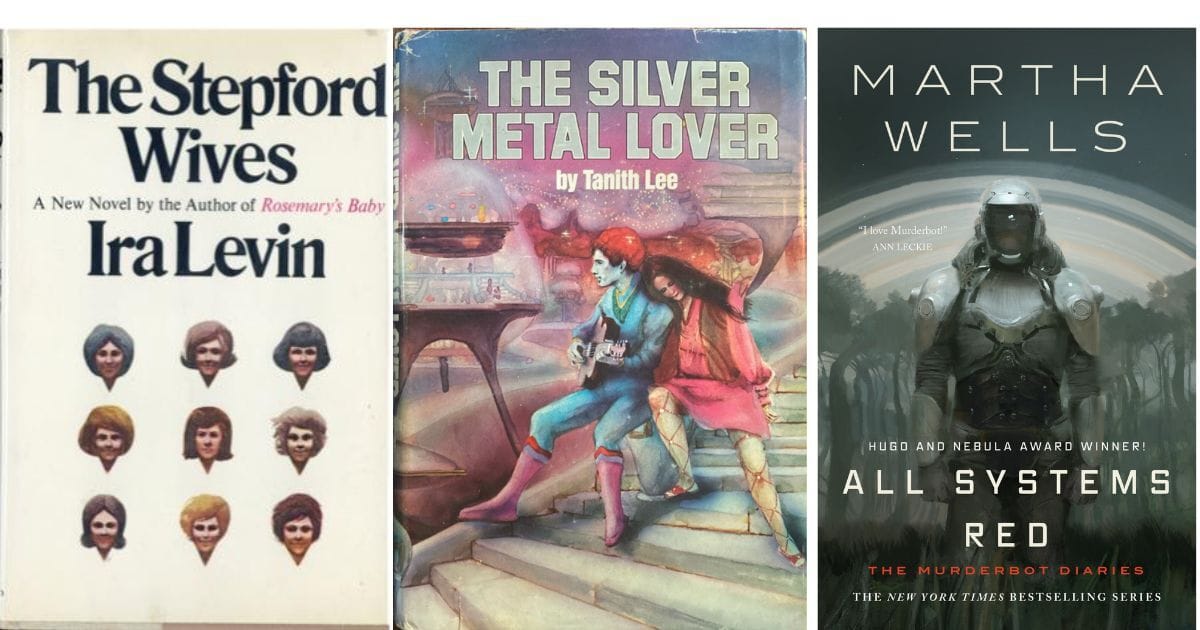

The Stepford Wives (1972)

Ira Levin

A razor-edged suburban fable: in Stepford, the husbands’ club replaces women with compliant replicas. Levin’s “robots” are instruments of patriarchal restoration: automata as ideology made flesh. First received as horror-satire (and later a cultural shorthand: “Stepford wife”), the novel entwines technology with control over identity and labor in the home. Robotics is less about metal than power, gaze, and the engineering of consent.

The Silver Metal Lover (1981)

Tanith Lee

A lush, subversive romance between a privileged young woman and an entertainment android engineered to be irresistible. Lee flips the male-inventor/ideal-woman script and writes desire, art, and autonomy from the other side of the gaze. The tech is soft—corpocratic product design tuned to the human heart, and that is the point: commercialization of intimacy. Critically admired and cult-beloved, it remains a touchstone for debates about consent, commodification, and whether programmed love can grow into something real.

All Systems Red (The Murderbot Diaries #1) (2017)

Martha Wells

Goodreads

A corporate-leased SecUnit hacks its governor and would rather binge serials than babysit humans, until real danger forces real choices. With brisk humor and moral clarity, Wells captures a new robot frontier: contract labor, surveillance capital, and the fight for personhood inside a stitched-together human/machine supply chain. Reception was rapturous, and the series has become the contemporary standard for voice-driven robot autonomy. A crisp modern endpoint to this lineage.

Ink & Time Curated Tuesdays brings you thematic book recommendation bundles to inspire literacy, and expand your world.