"When you don't know what you're living for, you don't care how you live from one day to the next. You're happy the day has passed, and the night has come."

So sighs Ilya Ilyitch Oblomov, in the opening chapters of Goncharov’s masterpiece. We find our charming but unmotivated feudal lord musing on all matters of life, love, meaning and simply... whether or not to get out of bed.

It’s easy to dismiss or even disdain him for being lazy.

But is that response merely a function of a market-driven mindset which celebrates the “hustle culture?”

The sad reality is that most employees work hard every day without really knowing why. They push and fight for no apparent reason except as part of their striving to accumulate greater financial resources.

You can read Chapter 1 of Oblomov here:

For companies, the crisis of purpose has become existential

Fast forward to 2025. According to a recent Gallup survey, half of U.S. employees now qualify as "not engaged." We all know those zombie-like employees, commonly referred to as "quiet quitters," or those who "lie flat."

Worldwide, just 21 percent of workers reportedly give a damn about their jobs. The memes speak volumes: "Act your wage," "Bare minimum Mondays," "I'm not lazy, I'm on energy-saving mode."

Behind the troubling numbers lurks a pervasive disquiet, part ennui, part fatigue, part muted protest. The workers are restless, bored, and at times perhaps even feeling vaguely guilty. It's a similar emotional cocktail conceived by Goncharov in 1859.

It’s more than BS. Anthropologist David Graeber surveyed workers in Britain and Holland and discovered that up to 40 percent believed their jobs made no meaningful contribution to the world. He famously called their positions “bullshit jobs.”

It’s a modern, ironic twist on the Oblomovian mindset. They’re not idlers; many juggle relentless Zoom calls, slide decks, and compliance trainings. Yet they share Oblomov's existential dread: What if none of this means anything?

A portrait of honest reflection: On purpose, and it’s absence

Our friend Oblomov, bless his heart, is very clear that he is not interested in hustling or bustling, nor trying to socialise and seek approval from others who he believes have superficial motives. He muses:

“Yesterday one has wished, today one attains the madly longed-for object, and tomorrow one will blush to think that one ever desired it.”

Does his detachment make him an inherently bad person? Not in my view. But it depends on your ideological outlook.

Reading Goncharov's beautifully written prose of Oblomov's inner dialogue, we see he is a good person with a good spirit. He is a rare breed who is honest in his self-reflection about his life. In his case, it is also darkly ironic.

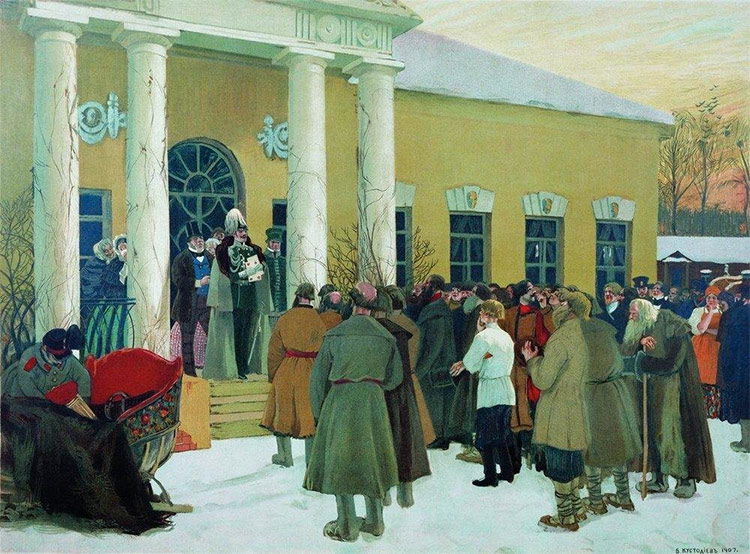

The unfortunate reality is that he lives purely off the labour of others. As a rent-seeking feudal lord, albeit a slacker, he has the luxury not to care.

Oblomov's Petersburg lifestyle is bankrolled by some 300 serfs breaking their backs in distant fields. Captured through his utopian dreams, we see no recognition of the oppressive physical labor that undoubtedly supports the functioning of Oblomovka. In his daydreams, he drifts back to his childhood estate, where summer afternoons stretched endlessly and nobody ever raised their voice. It is an agrarian heaven edited of all struggle and conflict.

Yet it exposes a universal nostalgia for a simpler, safer tempo of life. It’s a fantasy many of us secretly cherish, that somewhere, somewhen, life was simpler, safer, slower, and perhaps more humane.

Upon closer examination, one wonders if such a serene, peaceful life as charmingly described, the life without need for any serious consideration, an absence of ambition, concern or meaningful struggle, is really so idyllic after all.

Would any of us want to live in such a contrived paradise? Is it in fact devoid of something essential to the human experience? Has it thus doomed children like little Oblomov to an attitude of detachment or even fear of real purpose?

Purposeful, productive work, most of us accept, is an essential part of living a full human life, even if that work is not singularly focused on commercial gain.

From Superfluous Man to Superfluous Professional

The tension between idleness and industry forms Goncharov’s central social critique of late-stage feudalism in Russia, circa 1860. Oblomov is the archetypal “Superfluous Man.”

It is his unearned economic insulation that led radical critic Nikolay Dobrolyubov to diagnose Oblomovism as a “disease of landed entitlement,” a social pathology rotting the Russian society at its core. Idleness ceases to be a vice of temperament and becomes rather a structural defect of the class system.

Here it’s worth remembering that serious people believe we have entered early-stage techno-feudalism whereby a platform gentry lord over cloud-based serfs. That’s for a later deeper dive.

Oblomov is at once prototype, political symbol, tormented soul, and contemporary provocation. Goncharov created him as a comic portrait of the mid‑nineteenth‑century Russian landlord who will not bestir himself and contributes no economic value to speak of.

Productive work has literally been outsourced to people he rarely meets. For this reason, Oblomov could never be a quiet quitter in the modern sense of the term.

A quiet quitter withholds discretionary effort within an economic structure of a wage contract. His idleness therefore cheats the owner of the commercial enterprise who is paying for his labor and time, as agreed.

It's a behaviour one can rationalize and debate based on equity or ethics, or both. Oblomov and his ilk drift far above the whole edifice of wages, secure on a cushion of passive rent.

As historian Michael Lynch notes, by the 1850s Russia’s ruling elite “resembled a class living off the memory of usefulness.” Tsar Alexander II’s Emancipation Edict of 1861 would soon upend the economic arrangement, but not before Goncharov captured its ironic ethos in a single supine figure. His timing was impeccable, and the legacy of the icon he created has endured.

Oblomov therefore became more than a singular character. The concept of being an Oblomov entered the popular lexicon and became representative of the pervasive criticism of a parasitic elite that was eroding Russian society from the inside.

Indeed, Lenin was fond of referencing him, as he did in a speech in 1922:

“There was a character who typified Russian life, Oblomov. He was always lolling on his bed and mentally drawing up schemes…. Russia has experienced three revolutions, but the Oblomovs have survived, for there were Oblomovs not only among the landowners but also among the peasants; not only among the peasants, but among the intellectuals too….

As we wait anxiously on the cusp of widespread automation and labour displacement, when especially for knowledge workers, the concept of the “superfluous man” morphs into the “superfluous professional,” it is worth interrogating the supposed merit of industry without purpose.

Equally profound, the absence of contemplation is a tragic loss of something essentially human and in a digital-first society, it appears to be accelerating.

When productive effort is neither required of the owner nor adequately rewarded to the administrator, why not stay in bed?

Re‑thinking Idleness: From Personality Flaw to Subtle Protest

Oblomov's refusal to join the rat race is easy to mock. Is it laziness? Or is it unintentionally, a form of silent protest? His seemingly dysfunctional lifestyle, his sweet antagonistic mindset, can be viewed as a negative critique of the system that sustains him.

By refusing to pursue a ministry posting or even to exercise the minimum management of his estate, he deprives a decadent order of the appearance of dignity and vigour. He refuses to play the game.

His immobility embarrasses every bustling friend who storms through his drawing room, those who are convinced that motion equates to meaning. The characters we meet – Schtoltz, Tarantiev, Olga – represent a cross-section of the shifting Russian society and their attitudes toward Oblomovism. They portend analogous ambitions, and anxieties, in our 2025 social construct.

Goncharov himself was not purely critical of our dear lazy aristocrat:

"Even were a whole ocean of evil and rascality to come seething about him, and even were the whole world to become infected with poison and be turned upside down, Oblomov would yet refuse to bow to the false image, and his soul would remain as clean, as radiant, and as without spot as ever."

Meanwhile, some of his friends in the story envy Oblomov’s sense of peace and calm, just as office workers day‑dream about one day logging off, despite their mobile phone addictions.

Today’s disengaged employees, by quietly limiting their labour to the contractual minimum, puncture the corporate self‑image and the merits ascribed to a universal hustle. Productivity reports become performative. Executive management fret about “employee engagement.”

In both eras, the absence of voluntary zeal is perhaps less an indictment of individuals and more an exposure of structural hollowness in our economic system.

Goncharov’s story is a timeless reminder and two-fold warning. Privilege without purpose metastasizes into parasitism. The daily grind without meaning eventually ferments into disengagement and depression. Labor that offers no intrinsic or social rationale eventually starves motivation. Either outcome, cushioned torpor or frenetic vacancy, signals a social contract under strain.

Dive into the tension between stillness and action with Oblomov

An Eternal Human Tension: Stillness versus Action

Beyond its political economic satire, Oblomov stages a commentary about the purpose of life itself. It becomes something of a philosophical cage match most of us can relate to.

On one side stands our anti-hero’s ideal of stillness, a condition he associates with honesty, emotional safety, and the ability to savor beauty.

On the other side stands his half‑German friend Schtoltz, an apostle of action, who believes identity is forged in work and civic engagement. The two ideals are like opposing poles, generating engaging tension that lights up the book.

Modern culture has yet to resolve this tension; both sides have been monetized. The wellness industry peddles overpriced stillness in the form of meditation apps and silent retreats. The hustle shop sells expensive urgency through productivity courses and life-hacking guides. Goncharov refuses to pick a winner and instead forces us to meditate on the discomfort.

These are difficult questions that haunt the novel, and should haunt us: What kind of action deserves our energy and enthusiasm? It is probably not the quarterly reports.

What kind of stillness actually nourishes rather than numbs? Doom scrolling might feel like rest, but it actually sucks vitality.

Habitual numbing out takes its toll on poor Oblomov. Try reading Part IV without slipping into a feeling of empathy and genuine sadness over his fate, and the degenerative effect of a lack of meaning in life.

Ink & Time provides thought provoking curations from lost or forgotten books because we believe real literacy is key to better thinking, and more happiness.