One in five adults in the U.S. are chronically lonely. Are you one of them?

Mental health professionals have declared loneliness a "public health crisis", despite hyper-connectivity and always-on social media. Is it our fault?

Or is it an essential feature of living in modern society?

Over a century ago, during Japan's headlong rush into modernity, novelist Natsume Sōseki diagnosed the affliction. His 1914 masterpiece Kokoro (meaning "heart" or "the core of things") delivered the shocking prognosis:

"Loneliness is the price we have to pay for being born in this modern age."

As isolation reaches epidemic proportions, did this Meiji novelist identify a universal law of modernity? Is loneliness a feature, rather than a bug?

For a deeper dive on the modern Loneliness Epidemic check these links:

American Psychiatric Association Poll Full report

30% of adults experience weekly loneliness (10% daily), with singles (39%) and adults under 35 (30%) disproportionately affected. While 75% credit technology for enabling connections, 54% feel these relationships are superficial.Pew Research Center Survey Full report

1 in 6 Americans reports chronic loneliness, with under-30s twice as likely as over-65s to feel isolated. Younger generations rely on texting/social media , while older adults prioritize face-to-face engagement.Cigna Healthcare International Study Full report

Gen Z (ages 18–27) scores 48.3 on the UCLA Loneliness Scale: 25% higher than the Silent Generation (38.6). Loneliness correlates with poor sleep (50% higher risk) and physical health declines.Harvard Magazine Analysis Full report

Existential loneliness affects 61% of adults post-pandemic, with 18–24-year-olds most vulnerable. Societal exclusion (racism, disability stigma) compounds isolation, while "meaningful connection gaps" persist despite digital tools.

If you’re interested in the topic of loneliness, here is a counterpoint from the Ink & Time archives. Oblomov exhibits a different approach to solitude, enjoying the retreat from the bustle of society:

Sōseki's Uneasy Heart

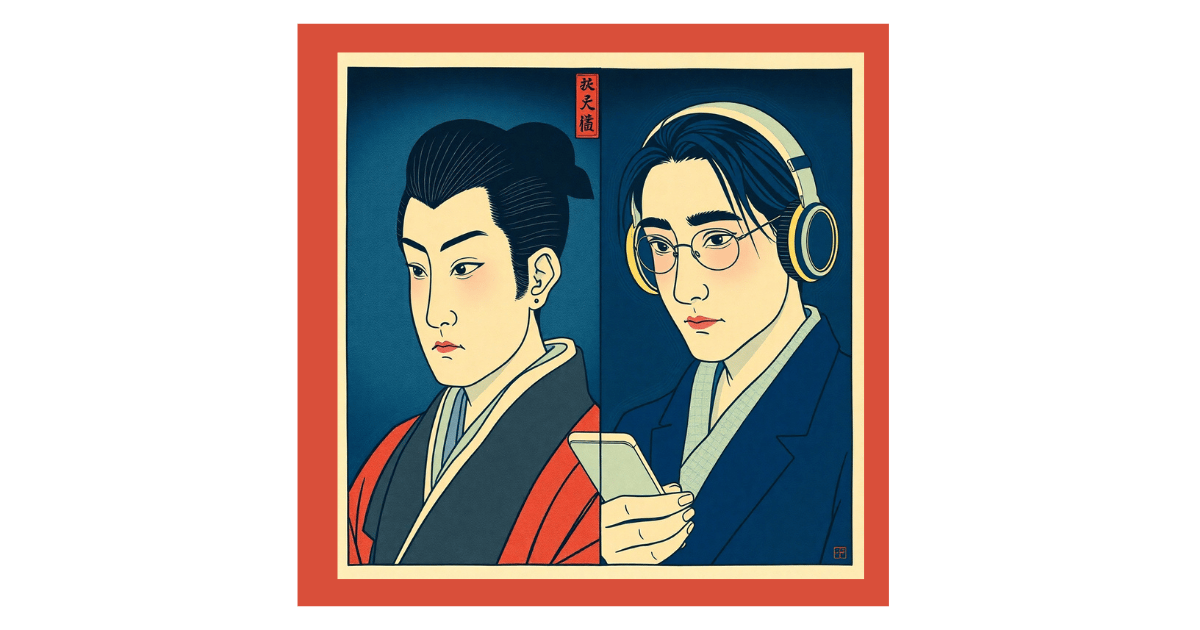

Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916) was born at the dawn of the Meiji Restoration, witnessing its dizzying modernization, a transformation from isolated feudal society to an industrial power that defeated Russia in the war of 1899.

Unlike many who celebrated rapid progress, Sōseki harbored deep misgivings about modernity. Trained as an English literature scholar, he spent two years in London on a government scholarship, an experience that left him profoundly alienated and disillusioned with Western "civilization." He returned to Japan only to find his home country racing toward the same spiritual emptiness he detected abroad.

Turning to fiction after a nervous breakdown, Sōseki was Japan's first novelist to vividly portray "the plight of the alienated modern Japanese intellectual." His protagonists were often educated men caught between traditional values and Western individualism, struggling to maintain authentic human connections.

Kokoro, serialized in 1914, was Sōseki's late-career masterpiece. The novel unfolds against the backdrop of Emperor Meiji's death, a pivotal moment symbolizing the end of an era. The story follows a young university student who befriends an older mentor he calls "Sensei," only to discover the tragic secret that led this respected figure to live in self-imposed isolation.

The novel's innovation lay in its unflinching psychological depth. When most Japanese writers were celebrating national progress or focusing on external social conflicts, Sōseki turned inward to examine the hidden costs of modernization: loneliness, moral confusion, and the pain of disconnection that progress couldn't cure.

Here is a translation by Edwin McClellan, 1957 now in the public domain.

You can read the original in Japanese at the Soseki Project

Prophecies on Being Modern while Being Human

"You see, loneliness is the price we have to pay for being born in this modern age, so full of freedom, independence, and our own egotistical selves."

Sensei bluntly pinpoints a paradox that has intensified in the past 100 years: the very freedoms modern life gives us (to pursue our own path) lead to profound isolation.

At the time, Japan was new to urban anonymity and Western individualism. Today, social scientists have confirmed that societies focused on individual autonomy report higher rates of loneliness than community-oriented cultures.

"Youth is the loneliest time of all."

You might assume an elderly widower is the loneliest, not a student with a full life ahead. Yet Sensei perceives that young people, severed from traditional support structures but not yet settled in adult identity, face uniquely severe isolation.

Research indicates that people aged 16 to 24 are more likely to feel lonely than those over 75, with some studies showing that up to 40% of younger individuals report loneliness compared to about 27% of those over 75.

"Perhaps you will not understand clearly why I am about to die... You and I belong to different eras, and so we think differently. There is nothing we can do to bridge the gap between us."

In his final letter, Sensei acknowledges an unbridgeable generation gap. Value systems shift so dramatically that full understanding becomes impossible.

He anticipates the modern friction between Boomers, Millennials, and Gen Z.

Sōseki foresaw that modernization would fragment society by age cohort, creating knowledge and value systems that barely overlap. His pessimism about bridging these gaps raises uncomfortable questions about our own divided era.

Is it ever possible to overcome the division Sensei considered inevitable?

The Quiet Pervasiveness of Kokoro

Many Japanese trace the lineage of introspective, confessional novels back to Kokoro.

Osamu Dazai's dark classic No Longer Human (1948), a postwar tale of alienation, is often seen as its spiritual successor. Together, these two novels remain among Japan's all-time bestsellers.

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, famed author of Rashōmon, openly revered Sōseki; a letter of praise from Sōseki in 1916 jump-started his literary fame.

Even mid-century authors like Yukio Mishima and Kenzaburō Ōe drew on themes Sōseki pioneered, the clash between tradition and modernity, the crisis of identity.

More recently, internationally acclaimed novelist Haruki Murakami has cited Sōseki as his favorite Japanese writer, crediting him with inspiring his blend of Eastern and Western storytelling.

His legacy also appears in philosophy classrooms as a case study in modern ethics. In pop culture, the story has been repeatedly adapted for film and television, and even reimagined in anime series.

For decades, Sōseki's face graced the ¥1,000 banknote (1984-2007) as testament to his stellar cultural impact.

His lecture "My Individualism" (1914), anticipated the loneliness and identity crises of our hyper-modern age. Some scholars dub Sōseki a prophet of modern malaise, noting how accurately he foresaw the psychological toll of unfettered individualism.

Lessons on Being Alone in “Civilized Society”

Kokoro distills timeless lessons about loneliness and morality in a changing world.

Freedom vs. Connection

Meiji Japan's rush to individualism left characters like Sensei feeling cut off. Western societies experienced a similar trade-off as traditional communities gave way to city life. People thought they wanted anonymity, but for many it turned into a curse.

The Weight of Guilt

Sensei's life is crippled by guilt over betraying someone he loved. Unresolved guilt can become a lifelong burden. Western literature, from Dostoevsky to Graham Greene, portrays modern individuals wracked by conscience in an era of fading moral certainties.

Trust in an Uncertain World

Having been betrayed, Sensei concludes that "one must always be on guard." He trusts no one, not even himself. His extreme cynicism serves as a cautionary tale. After the upheavals of the 20th century, Western intellectuals also became skeptical of grand ideals. While healthy skepticism is wise, complete distrust is isolating.

Meaning in a Material World

Beneath all its personal drama, Kokoro asks the difficult question of how to find meaning when old spiritual certainties fade. Sensei cannot lean on feudal codes nor fully embrace new consumer pleasures. He's become spiritually adrift.

In the West, after Nietzsche declared "God is dead," people struggled to find purpose in a secular, commercial age.

Indeed, one could say now that shopping has become a surrogate spiritual pursuit, in the absence of formal religion for many. Modern life offers endless distractions.

Read books, it helps. This is the purpose of Ink & Time. Share with your friends.

Interested in Kokoro? You might like these too:

Sanshirō (Natsume Sōseki, 1908) – Another Sōseki gem, this novel follows a young man from the countryside navigating Tokyo University's bewildering environment. Sanshirō's mix of curiosity, loneliness, and romantic confusion gently satirizes the Meiji era's clash of tradition and modernity.

The Wild Geese” (Mori Ōgai, 1913) - Set in the Meiji era, it follows a young woman caught in arranged concubinage and a student torn by Confucian ethics and personal feeling, paralleling Kokoro’s themes of unrequited love and social constraints.

The Beast in the Jungle (Henry James, 1903) - James’ hero, burdened by moral inaction or failure, waits for a fateful event in vain, in a similar exploration of guilt, self-absorption and existential waiting, not unlike Kokoro’s.

No Longer Human (Osamu Dazai, 1948) – A candid, haunting look at alienation in 20th-century Japan. Told through the notebooks of a man who feels "disqualified" as human, Dazai's semi-autobiographical novel examines depression, addiction, and the masks we wear. It's often ranked alongside Kokoro as one of Japan's best-selling novels about the ache of not fitting in.

In an age of smartphones and AI agents, are we any less isolated at heart than Sensei was in Tokyo a century ago?

Share your thoughts in the comments.

In Kokoro, a wise yet wounded man reaches across a societal divide to confess his truth.

The most resonant insight: no one is truly alone in feeling alone.

Over a hundred years later, we're still grappling with how to live as free individuals without becoming isolated souls.

If you enjoyed this one, or even if it made you feel a bit lonely, hit subscribe and make some new friends exploring books from an analog era.

Ink & Time is dedicated to fostering book discovery, promoting real literacy, and curating perspectives from forgotten books that are highly relevant to today’s world.