Have you watched, or read A Christmas Carol this year?

Ebenezer Scrooge and the Christmas Ghosts have become icons of the season, alongside Santa, the Grinch and Charlie Brown.

Year after year, we return to Charles Dickens for a reliable injection of vicarious redemption, comforted by the certainty that the ghosts will arrive on schedule and moral order will be restored before the turkey is carved.

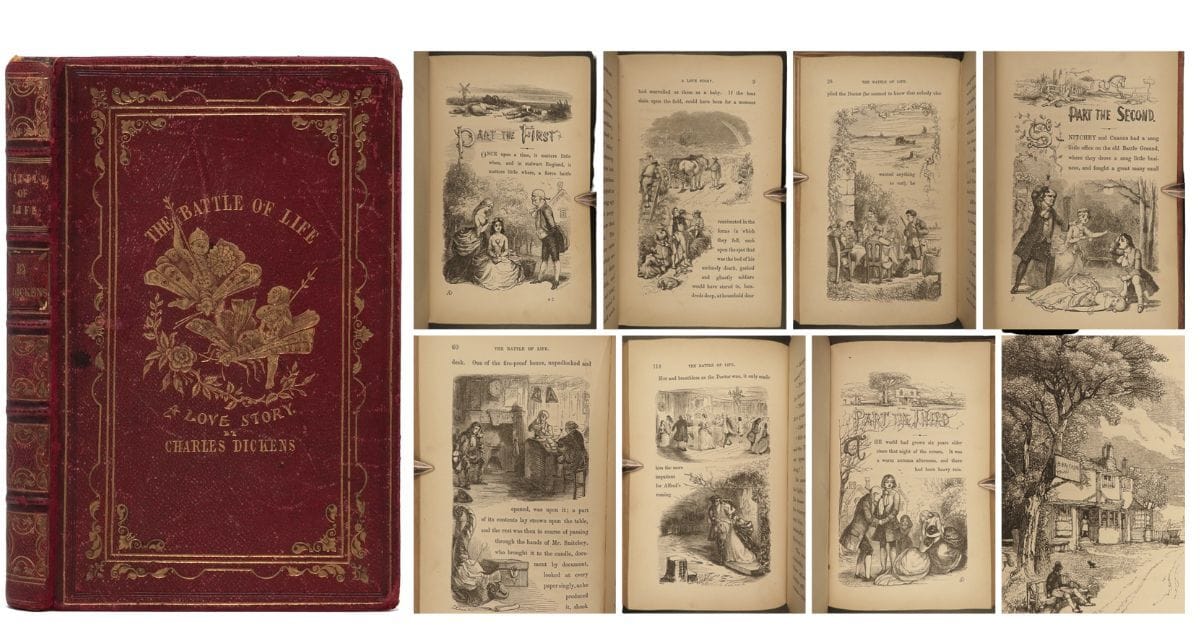

Dickens wrote five Christmas books, though we only remember the one. There was another that was so despised upon publication in 1846 that The Times labeled it "the very worst." Modern critics call The Battle of Life "saccharine" and note its distinct lack of "yuletide cheer.”

They’re right. It’s barely a Christmas story by contemporary standards. There’s no mistletoe, no snow-sledding, and no supernatural spirits to force a change of heart.

Yet, the absence of festive machinery is part of what makes this Dickens tale particularly relevant today. Stripping away the safety net of ghostly intervention, Dickens forces us to confront a stark question:

How do we maintain a moral existence on ground saturated by violence and struggle?

Striving for the authentic spirit of the season, this edition of Ink & Time remembers The Battle of Life, Dickens’ least known and most harshly criticized Christmas book.

Few could now read the text in full, given the deterioration of attention and the patience his prose requires. That’s why we’re here: to bring you forgotten classics, encourage reading, and help you extract the essence of the story to enrich your life.

But don’t stop here. The full text of The Battle of Life can be read here.

A Very Un-Christmas Story with a Christmas Message from Charles Dickens

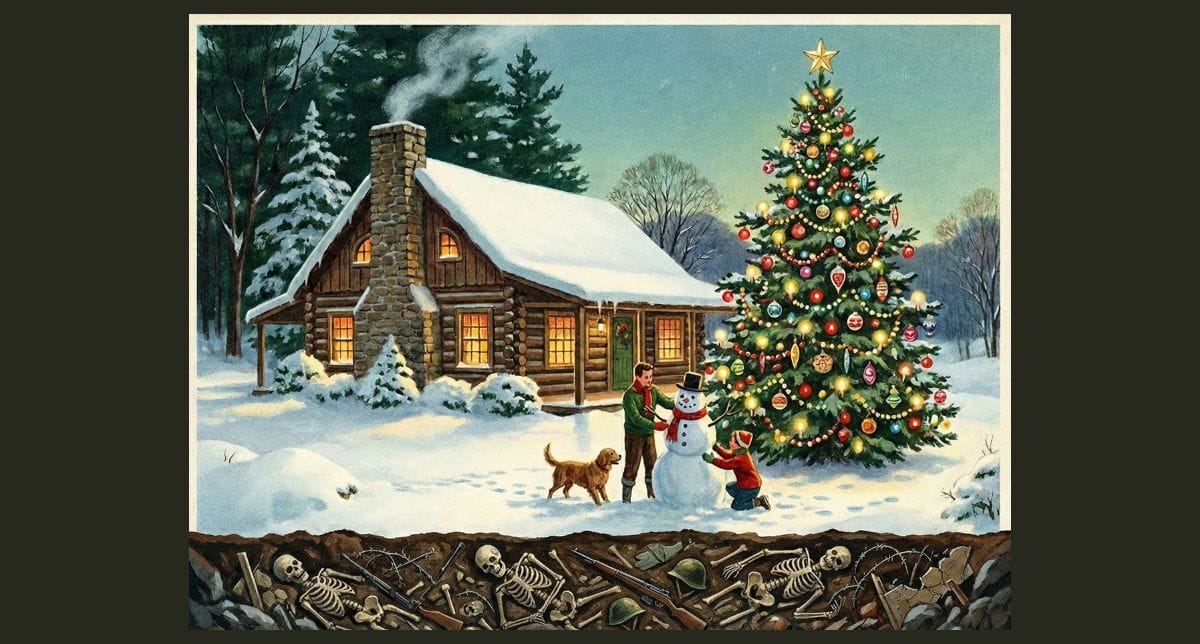

In a classically un-Christmas sort of way, the story begins not next to a warm cozy hearth, but with remembrance of a literal battlefield.

Dickens describes an ancient slaughter where streams ran red and bodies were plowed under a "quagmire." The setting takes place on top of a historic battleground. Time has passed. Nature has recovered her serenity. A quiet English village sprouts up on the site of the atrocity.

Heaven keep us from a knowledge of the sights the moon beheld upon that field, when, coming up above the black line of distant rising-ground, softened and blurred at the edge by trees, she rose into the sky and looked upon the plain, strewn with upturned faces that had once at mothers’ breasts sought mothers’ eyes, or slumbered happily.

Heaven keep us from a knowledge of the secrets whispered afterwards upon the tainted wind that blew across the scene of that day’s work and that night’s death and suffering! Many a lonely moon was bright upon the battle-ground, and many a star kept mournful watch upon it, and many a wind from every quarter of the earth blew over it, before the traces of the fight were worn away.

Then, he drops a hard-hitting image, one that if we read closely and attentively, captures our modern relationship with trauma:

“The wounded trees had long ago made Christmas logs, and blazed and roared away.”

The physical traces of suffering are literally carried indoors and burned for warmth. Far from remaining a testament to the scars of war, and the human lives lost in the fight, the trees themselves become no more than fodder for forgetting.

In 2025, it’s a metaphorical indictment of our perverse proclivity to normalize horror.

We scroll past real-time atrocities in Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan and elsewhere, briefly shocked, before the algorithm feeds us a cooking video, or a holiday kitten, or some other psychological balm.

It’s not that we are inherently callous. We are inclined to ignore and forget, because appreciating distant violence, and feeling kinship with those who suffer, is incompatible with feeling satisfied, self-assured, and just getting on with our day. Paralyzing grief at the suffering in the world prevents the continuous consumption that keeps the economy humming.

Like Dickens’ villagers, we build our daily lives on top of unacknowledged battlefields, past and present, physical and psychological. His characters inhabiting this normalized ground represent coping mechanisms we can all recognize and relate to.

The patriarch, Dr. Jeddler, insulates himself from the horrors by treating life as a joke. Having lived his whole life on a graveyard, he argues that if you take the world seriously, "you must go mad, or die."

His laughter is a defensive anesthesia against the overwhelming contradiction.

‘Of all days in the foolish year. Why, on this day, the great battle was fought on this ground. On this ground where we now sit, where I saw my two girls dance this morning, where the fruit has just been gathered for our eating from these trees, the roots of which are struck in Men, not earth; so many lives were lost, that within my recollection, generations afterwards, a churchyard full of bones, and dust of bones, and chips of cloven skulls, has been dug up from underneath our feet here.

‘Yet not a hundred people in that battle knew for what they fought, or why; not a hundred of the inconsiderate rejoicers in the victory, why they rejoiced. Not half a hundred people were the better for the gain or loss. Not half-a-dozen men agree to this hour on the cause or merits; and nobody, in short, ever knew anything distinct about it, but the mourners of the slain. Serious, too!’ said the Doctor, laughing. ‘Such a system!’

‘But, all this seems to me,’ said Alfred, ‘to be very serious.’

‘Serious!’ cried the Doctor. ‘If you allowed such things to be serious, you must go mad, or die, or climb up to the top of a mountain, and turn hermit.’

Dr. Jeddler has sunk into a well-trodden attitude of resigned cynicism, even fatalism, deferring to a common defense mechanism of levity and humor.

He is also darkly honest about how pervasive and deeply ingrained the spirit of battle has become.

‘I am too old to be converted, even by my friend Snitchey here…. I was born upon this battle-field. I began, as a boy, to have my thoughts directed to the real history of a battle-field. Sixty years have gone over my head, and I have never seen the Christian world, including Heaven knows how many loving mothers and good enough girls like mine here, anything but mad for a battle-field.

‘The same contradictions prevail in everything. One must either laugh or cry at such stupendous inconsistencies; and I prefer to laugh.’

Why accepting challenge and struggle is the only way to improve and benefit others

In contrast, the sharp-elbowed lawyers Snitchey and Craggs see life as a perpetual, vicious competition for status, for gain, for advantage: ”cutting and slashing" and "firing into people’s heads from behind."

It’s the alternate reaction, from a realist point of view; There are those who default to viewing society as ruled by the law of the jungle, dog eat dog, kill or be killed.

‘I don’t stand up for life in general,’ he added, rubbing his hands and chuckling, ‘it’s full of folly; full of something worse. Professions of trust, and confidence, and unselfishness, and all that! Bah, bah, bah! We see what they’re worth.

‘But, you mustn’t laugh at life; you’ve got a game to play; a very serious game indeed! Everybody’s playing against you, you know, and you’re playing against them. Oh! it’s a very interesting thing. There are deep moves upon the board. You must only laugh, Dr. Jeddler, when you win, and then not much,’ repeated Snitchey, rolling his head and winking his eye.

Yet, it is Craggs who offers a surprising critique of the modern impulse toward seeking maximum comfort and convenience, something we should all take note of.

There is value in taking the difficult path, or even in being made to wait and to struggle. Sometimes this is the only way to be of benefit to others, as we will see.

‘The French wit,’ said Mr. Snitchey, peeping sharply into his blue bag, ‘was wrong, Doctor Jeddler, and your philosophy is altogether wrong, depend upon it, as I have often told you. Nothing serious in life! What do you call law?’

’ A joke,’ replied the Doctor.

‘Did you ever go to law?’ asked Mr. Snitchey, looking out of the blue bag.

‘Never,’ returned the Doctor.

‘If you ever do,’ said Mr. Snitchey, ‘perhaps you’ll alter that opinion.’

Craggs, who seemed to be represented by Snitchey, and to be conscious of little or no separate existence or personal individuality, offered a remark of his own in this place. It involved the only idea of which he did not stand seized and possessed in equal moieties with Snitchey; but, he had some partners in it among the wise men of the world.

‘It’s made a great deal too easy,’ said Mr. Craggs.

‘Law is?’ asked the Doctor.

‘Yes,’ said Mr. Craggs, ‘everything is.

‘Everything appears to me to be made too easy, now-a-days. It’s the vice of these times. If the world is a joke (I am not prepared to say it isn’t), it ought to be made a very difficult joke to crack. It ought to be as hard a struggle, sir, as possible. That’s the intention. But, it’s being made far too easy. We are oiling the gates of life. They ought to be rusty. We shall have them beginning to turn, soon, with a smooth sound. Whereas they ought to grate upon their hinges, sir.’

Mr. Craggs seemed positively to grate upon his own hinges, as he delivered this opinion; to which he communicated immense effect—being a cold, hard, dry, man, dressed in grey and white, like a flint; with small twinkles in his eyes, as if something struck sparks out of them.

We live in an era optimized for smoothness. Our entire economy exists to eliminate friction: one-click ordering, algorithmic curation, relationships managed via apps. Most of us have more than enough, but we pay more to remove every “inconvenience,” or to enhance little by little, our experience of comfort in life.

Life should be frictionless, we are told, and surely we will be happier.

Craggs argues that a rusty gate forces a much needed pause. Resistance is vital. Friction is where we gain traction. It’s in the difficult conversation, the inconvenient duty, and the painful choices in which character is formed.

Indeed, it is only through struggle and hardship that we really grow.

First edition of The Battle of Life, by Charles Dickens (1846)

Dickens tests these opposing philosophies within the claustrophobic confines of Jeddler’s home. The domestic drama that unfolds is the "battle of life" in situ, and in miniature.

Jeddler has two daughters, Grace and Marion. Marion is engaged to Alfred, who leaves to study, promising to return for her after a year. But the playboy, Michael Warden, appears ready to seduce Marion away. The crisis erupts when Marion disappears on the very day Alfred returns and when the village is enjoying a great Christmas celebration.

The village assumes a scandalous elopement with Warden. Hearts are broken in this microcosmic "battle of life.” Her sister Grace, suppressing her own love for Alfred, nurses him through his grief. Eventually, they get married.

When Alfred returns to the village, he is described thus:

He had not become a great man; he had not grown rich; he had not forgotten the scenes and friends of his youth; he had not fulfilled any one of the Doctor’s old predictions. But, in his useful, patient, unknown visiting of poor men’s homes; and in his watching of sick beds; and in his daily knowledge of the gentleness and goodness flowering the by-paths of this world, not to be trodden down beneath the heavy foot of poverty, but springing up, elastic, in its track, and making its way beautiful; he had better learned and proved, in each succeeding year, the truth of his old faith.

The manner of his life, though quiet and remote, had shown him how often men still entertained angels, unawares, as in the olden time; and how the most unlikely forms, even some that were mean and ugly to the view, and poorly clad, became irradiated by the couch of sorrow, want, and pain, and changed to ministering spirits with a glory round their heads.

He lived to better purpose on the altered battle-ground, perhaps, than if he had contended restlessly in more ambitious lists.

Only years later does the truth emerge, revealing the story’s true battlefield. Marion returns to explain she never eloped with Warden. She saw that her sister Grace truly loved Alfred. Thus, Marion’s disappearance was a profound, calculated act of self-abnegation to allow Alfred and Grace to find happiness together.

This is the friction, applied to the human heart. Marion did not merely step aside politely; she accepted social exile and the calculated destruction of her own reputation to ensure her sister’s happiness. A total self-immolation, a battle fought entirely in secret, with no hope of a medal.

Alfred becomes the story’s moral anchor to validate that sacrifice. He proposes that the truest battles aren't the noisy historical slaughters, but the internal landscape of emotional combat:

‘I believe, Mr. Snitchey,’ said Alfred, ‘there are quiet victories and struggles, great sacrifices of self, and noble acts of heroism, in it, even in many of its apparent lightnesses and contradictions, not the less difficult to achieve, because they have no earthly chronicle or audience, done every day in nooks and corners, and in little households, and in men’s and women’s hearts; any one of which might reconcile the sternest man to such a world, and fill him with belief and hope in it, though two-fourths of its people were at war, and another fourth at law; and that’s a bold word.’

What if the Christmas Spirit is not about abundance and comfort but rather about honesty and self-sacrifice?

It is not hard to see why The Battle of Life failed as popular Christmas entertainment and why it has fallen out of circulation today. Dickens refuses to provide redemption as spectacle. There are no easy spirits to manage our moral accounting.

Instead, resolution requires the hard labor of forgiveness. Dr. Jeddler must forgive Michael Warden; the sisters must reconcile the years of lost time.

‘It’s a world full of hearts,’ said the Doctor, hugging his youngest daughter, and bending across her to hug Grace, for he couldn’t separate the sisters; ‘and a serious world, with all its folly, even with mine, which was enough to have swamped the whole globe; and it is a world on which the sun never rises, but it looks upon a thousand bloodless battles that are some set-off against the miseries and wickedness of Battle-Fields; and it is a world we need be careful how we libel, Heaven forgive us, for it is a world of sacred mysteries, and its Creator only knows what lies beneath the surface of His lightest image!’

The deepest "Christmas" message here is not about abundance nor a comforting festive mood. It’s an invitation to resistance against the easy path of convenience, and of willful ignorance to the suffering in the world.

Do we allow the "wounded trees" of the past, and present, to become mere fuel for greater comfort? Or do we, like Marion, accept the friction of a difficult choice for the sake of another?

This Christmas, and as we look ahead to a new year, would we even consider pursuing personal challenge or hardship to enhance our moral fiber and capabilities?

Would we do it to benefit others, in the spirit of selflessness and giving?

Is Christmas too comforting? Tell us in the comments:

It is enough that at last she triumphantly produced the thimble on her finger, and rattled the nutmeg-grater: the literature of both those trinkets being obviously in course of wearing out and wasting away, through excessive friction.

‘That’s the thimble, is it, young woman?’ said Mr. Snitchey, diverting himself at her expense. ‘And what does the thimble say?’

‘It says,’ replied Clemency, reading slowly round as if it were a tower, ‘For-get and For-give.’

Snitchey and Craggs laughed heartily. ‘So new!’ said Snitchey. ‘So easy!’ said Craggs. ‘Such a knowledge of human nature in it!’ said Snitchey. ‘So applicable to the affairs of life!’ said Craggs.

‘And the nutmeg-grater?’ inquired the head of the Firm.

‘The grater says,’ returned Clemency, ‘Do as you—wold—be—done by.’

‘Do, or you’ll be done brown, you mean,’ said Mr. Snitchey.

‘I don’t understand,’ retorted Clemency, shaking her head vaguely. ‘I an’t no lawyer.’

More simply, would we choose to not avoid seeing and feeling the suffering of others, near and far, instead understanding it as part of the essence of being human.

The true essence of the spirit of Christmas.

Real life is a battle ground, physical, mental and metaphorical. That is Dickens’ message in his overlooked Christmas story. We are too ready to comfort ourselves with holiday cheer, even if it means averting our eyes from the reality of suffering.

Despite the critics’ bombs, and the fact that the book has disappeared from view, it’s a Christmas story worth contemplating.

Ink & Time resurfaces long lost works of literature and extracts the lessons we can use for life today, with a view to inspiring real reading, not just mindless scrolling.

Join us by subscribing for free. And kindly share with others who would benefit.